Turquoise, Water, Sky: The Stone and Its Meaning, opening April 13, 2014 at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, highlights the Museum’s extensive collection of Southwestern turquoise jewelry and presents all aspects of the stone, from geology, mining and history, to questions of authenticity and value.

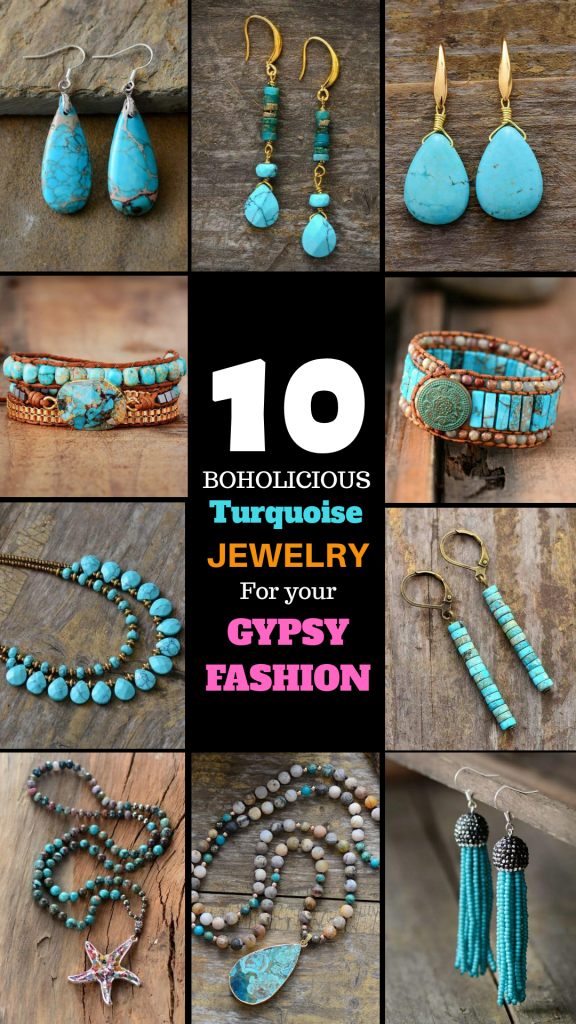

People in the Southwest have used turquoise for jewelry and ceremonial purposes and traded valuable stones both within and outside the region for over a thousand years. Turquoise, Water, Skypresents hundreds of necklaces, bracelets, belts, rings, earrings, silver boxes and other objects illustrating how the stone was used and its deep significance to the people of the region. This comprehensive consideration of the stone runs through May 2, 2016.

“Turquoise stands for water and for sky, for bountiful harvests, health and protection,” said Maxine McBrinn, Curator of Archaeology at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture. “Blue-green symbolizes creation and the hope for security and beauty. These ideas were so important that if the stone was not available, its color was represented through other methods.”

Color, Meaning, Value

Turquoise’s color reflects its environment. Nearby aluminum turns turquoise green. Zinc creates a yellowish green. Turquoise of the highest quality, holding the best colors, lies near the surface. Exposed to sunlight and weather, turquoise lightens.

Regardless of the color, turquoise holds prestige and power. Native American deities carry weapons and live in homes made of turquoise. The Apache believe turquoise filled the pot at the end of the rainbow. Zuni ceremonies include turquoise-colored face, mask, and body paint to represent Awonauilona, the sun’s life-giving power.

Its power is so great that no horseman would ride while carrying turquoise; it would tire the horse. Similarly, hunters drew lines with turquoise between the tracks of game to slow the game down. Hanging from bags in households, turquoise protects against misfortune.

Turquoise bracelets, necklaces and rings are wearable bank accounts; in the past, Native Americans used pieces as deposits for goods needed from traders. When they sold their crops or wool, the traders were paid and jewelry was reclaimed.

Mining History

It is estimated that Native Americans had been working with turquoise about 1200 years before the Spanish arrived, with the heaviest mining taking place between AD 1350 and 1600. Roughly 200 mines have been discovered throughout the Southwest, most believed to have been started by Native Americans, who used shaped stone hammers, mauls and adzes to chisel the pieces of sky out of the rock.

The largest ancient turquoise mine was found at Mount Chalchihuitl, near Cerrillos, NM. Some turquoise found at Chaco Canyon came from mines in the Cerrillos area, more than 150 miles to the southeast.

Native, Spanish and Moorish influences

Turquoise jewelry evolved as a companion of conquest.

In their 800-year reign of Spain, the Moors introduced crescent moons and the shape of pomegranate blossoms into Spanish culture. The Spaniards, seeking gold and silver, rode into Native American communities on horses wearing bridles bedecked with crescents.

The Navajo, especially, liked the symbol. They traded for it or captured it. The shape of the crescent became a naja at the base of a squash blossom necklace. Pomegranate blooms, a pattern used widely by the Spanish, inspired the squash blossoms themselves.

It is widely believed that the first recognized Native American blacksmith, Atsidi Sani, learned the craft from a Mexican blacksmith while touring “Navajo Land” with an American Indian agent in 1853. He may have added silversmithing to his skills during or after he was held prisoner at Fort Sumner, after he and his people were forced to relocate from Arizona.

Atsidi Sani and his students spread the skill. Zuni craftsmen learned the skill from Navajo teachers. Over the years, techniques and styles comingled, in lavish ways such as Navajo silver-stamped boxes decorated with Zuni inlay work.

Contemporary Artistic Expressions

Because of the work of contemporary Native art founders Charles Loloma, Kenneth Begay and others, current Native American jewelers no longer have to meet the expectations of viewers who only know Native American art as “traditional.”

Instead, they are free to merge their own inspirations with the skills and traditions they have learned throughout their lives.

Among them are Angie Reano Owen (Santo Domingo) – who, looking for a new avenue for creation amid the traffic jam of 1970s heishi, revived inlaid jewelry traditions – and Na Na Ping (Pascua Yaqui), whose elegant inlaid jewelry bears the work of a true lapidary, with stones that are meticulously cobbled together.

Both also took their paths away from tradition to reach their artistic vision. Owen merges the old (such as using wood as the backing for a bracelet) with the new (the black matrix that outlines each stone in her mosaics). Ping cuts stone with the skill taught to him by his uncles, but combines the stones in modernistic blends of color and angularity.

Like many modern Native jewelers, both are able to express their traditions in a contemporary voice.

TURQUOISE FACTS

Despite turquoise’s close identification in the US with the Southwest, other parts of the world have long held turquoise in high esteem.

Turquoise was used on the gold funeral mask of King Tutankhamen in Ancient Egypt.

- The oldest turquoise mines in the world, operated for thousands of years, are in Iran.

- The word “turquoise” comes from the French name for a beautiful blue stone they thought came from Turkey, but was actually from Persia.

- Turquoise is formed in arid regions by infrequent precipitation flowing through host rock and depositing minerals and salts. It is in these same regions – the US Southwest, central and northern Mexico, Andean South America, Tibet and Uzbekistan – that it is most valued as a gem stone.

- The Zuni word for turquoise can be translated as “sky stone.” This link between turquoise and sky is also true outside the Southwest; for example, in Tibet, the sky is sometimes called “the turquoise of Heaven.”

- Pueblo dancers wear turquoise regalia during the summer growing season to ensure rain.

- The stone’s color ranges from white (called chalk), to deep blue, pale blue, florescent yellow-green, deep green, and everything in between, but it’s the color and shape of the matrix, the veins of the host rock that run through turquoise, that contribute to its prestige and value.

- Turquoise is a soft stone and changes color as it is worn, becoming darker and greener. In many parts of the world it is believed that turquoise absorbs poisons and protect the wearer, or alternatively, that its color reflects the health of its wearer.

- Shell and turquoise are often used together. Both allude to water, one based on origin and the other on color, with the pairing intensifying the water symbolism.

- The Navajo link turquoise to protection and health. At birth, babies receive their first turquoise beads. The stone, in both whole and crushed form, is also included in puberty rites, marriage and initiation ceremonies, in healing ceremonies and other rituals. With the stone so intertwined with every stage of Navajo life, it is no coincidence that they are famed for their turquoise jewelry.